Transportation is the circulatory system of the world. From ants bringing food back to their nests to a 200,000 ton container ship bringing goods made in *insert country* to destinations across the world. Regardless of whether you care, understanding how the transportation systems that make up the fabric of our world are designed and function is important.

Background:

Wikipedia says that transportation is the movement of people, animals, and goods from one location to another. It also says that it can be broken down into three subdivisions - infrastructure, vehicles, and operations. Infrastructure being the fixed pathways such as roads, waterways, and railroads. Vehicles have been the feet beneath us all the way to jumbo jets. Operations deals with how we use these vehicles in the context of the infrastructure. I’ll tackle these three sections in kind, but I’ll start by saying that they are tightly interconnected; but I don’t think they quite have a chicken and egg relationship. At the very least I’d say that vehicles have informed what the infrastructure would be, which in turn has informed what the new vehicles would be, and so on. The operations side has always been the question of efficiency - of implementation - how do we use our systems.

Vehicles:

For the sake of simplicity, I think I’m going to skip past saying that walking was the first vehicle - combined with materials that float on water. Or that the wheel gave birth to variety of other methods of transport. That the engine opened up a world of possibilities when combined with those aforementioned structures. And that eventually the engine brought forth the possibility of adding wings and taking to the air and, ultimately, to space. All of that without even mentioning the set of methods that have been developed to transfer information and communicate(which I think deserve their own writeup. Coming soon™) . So, I lied - I didn’t actually skip all that much. I actually think it’s worth considering how far we’ve come. I say that because, despite how far we’ve come, it’s still important to consider whether our vehicles actually make sense.

For example, for a very long time, cars were designed with rear wheel drive even if the engine were at the front of the car. Physics logic finally caught up and said, “Huh, shouldn’t we use the engine to turn the wheels that are underneath it so that the normal force is maximized, which maximizes friction, which will let us accelerate more quickly.” Suddenly driving on more slippery surfaces became significantly easier without introducing the option of four-wheel drive. (Sidenote: Front wheel drive is made efficient by the use of transverse engines which turn an axel in the direction that the wheels turn, unlike a logitudinal engine which turns a drive shaft that runs along the length of a vehicle.)

Thinking critically about the design of things is important. Because, while it seems like a cool idea to push towards a future with flying cars like Back to the Future or Star Wars - is it a good idea? I don’t know. But, if we’re going to get to an answer to that question and several others, not only will we have to think critically about design, but also consider vehicles as a stand alone entity. If we continue to design vehicles with the existing infrastructure in mind, we’re almost guaranteed to miss something. That said, considering infrastructure is important. We don’t live in an idealized world. We have to consider everything.

Infrastructure:

So, infrastructure. The the stuff that planes, trains, and automobiles ride in or on. I know you don’t want me to do it...but I’m gonna do it anyway. It started with paths - animal tracks - rivers and oceans. Then we realized we could use rocks and other materials to make traversing them quicker and more stable. Even in the case of water, we learned to build canals to continue to travel by water even if it meant cutting through land. More recently, our atmosphere and the empty(ish) space beyond it have become our infrastructure.

Earlier, I made the point that our vehicles informed our transportation infrastructure. In my mind, the base level example of this is animal tracks. Passing over the same pieces of ground creates areas where vegetation doesn’t have time to grow to maturity - with a high enough frequency of travel, all that’s left behind is dirt. So, why is this relevant to a conversation about infrastructure? I’d have to say that it’s relevant because the development of the wheel came as a direct result of needing to traverse dirt efficiently. A hop, skip, and a jump down the line we have paved highways, the current pinnacle of ground transportation efficiency besides railroads. It may not be that obvious, but we design cars and trucks around being able to move quickly on paved roads. Of course there are exceptions, such as when you consider off-road vehicles. But think about it for a moment - there’s an entire industry built around the production of tires for vehicles that will be used primarily on paved roads. Those tires are designed for contact with with the materials that our roads are built out of. Most, if not all of the components of the vehicles that we use have been selected to optimize our travel across the existing infrastructure. Now of course, I don’t mean to say that the pinnacle of transportation technology is in use everywhere. But, where it’s been possible, we’ve pushed towards that upper limit.

When we plan for expansion, when cities are designed, we consider roads and subway systems as part of what would need to be included. Again, I have to pose a question - do roads make sense? They make sense in the context of our current vehicles. But, if again we peel away how we’ve chosen to design our infrastructure, what would make the most sense if minimizing the travel time between points was the goal? How would we be able to arrange buildings if accounting for road space between them wasn’t necessary? It would drastically change everything about how we move things and people from one place to another. What if standard building architecture included subway systems access a regular component of buildings? There’s an array of possibilities that I personally think we haven’t considered because we’ve been caught up in the design of vehicles and how best to operate within the infrastructure.

Operations:

So, that brings me to operations(I might call it ops periodically since I’m lazy). Although I consider it to be slightly independent of vehicles and infrastructure, operations is still a crucial aspect of transportation. It’s also useful that the operation of a transportation system is linked directly to the vehicles and infrastructure that define it. So, I’d say that when I think of operations, I think of the rules of the road. Stoplights, speed limits, and who’s driving the car; I think of the boarding and exiting of crowded subways in major cities; I think of the security line at the airport that inevitably takes longer than it should. Making sure that the who’s and the how’s make sense is a worthwhile endeavor. Even if implementation is hard to impossible, having an ideal to strive towards is preferable.

The information age has ushered in not only staggering access to data, but also to the computational power to analyze it in reasonable timeframes. Let me be clear, the field of study devoted to understanding and solving these type of complex problems didn’t come into existence as a result of computers. But computers have become central to continuing to push towards solutions as the problems have increasingly more constraints.

#Background complete - moving to phase 2

The world that is:

I was pushed to write this as a result of my daily commute. I mean, my sense of the importance of transportation to the function of the world came long before I had to commute anywhere, but the daily commute by bus to work catalyzed actually writing my thoughts down...coherently...maybe.

So, my commute seems like as good a place as any to start. I hop on the number 1 bus at the intersection of Mass Ave and Albany Street in Cambridge. From there I ride the bus all the way to Dudley Station. From Dudley station I transfer to either the 15 or the 41 bus for 6 more stops until I get off and walk the rest of the way to work(see map). On my way home, I do all of this in reverse. So, twice a day, 5 days a week, I’ve traveled the same pathway with minor deviations. It’s funny, at this point I’ve started to recognize all of the bus drivers, and, more often than not, there are familiar passengers on board.

Anyway, in these hours there have been multiple occasions when people have become frustrated with the amount of time the bus is taking to get them from point A to point B. The major sources are traffic, because the driver has decided to pick up more people when the bus is already pretty full, or because people are taking too long to get off or on because of payment issues or whatever else. I’d say that traffic isn’t usually complained about vocally, but you can see the impatience on people’s faces when the wall of cars ahead simply isn’t moving forward. Only once have I seen people start yelling at the driver for deciding to pick up more people. But every day there are at least a few people who inevitably get on the bus with cash and need to fight with their bills to get them into the slot or, possibly more common, don’t have enough money to ride. My sense is that these problems face people in metropolitan areas across the United States and I’m sure across the world as well. And this is for buses.

How does the current system fare when we consider subways, railroads, airplanes, and boats? (see pie chart(s) of travel times - also coming soon™) I can say with certainty, that we can do better. But, I’d also say that we as individuals can do a better job of understanding how we can make the system run more smoothly. That moment when people were angry with the bus driver and weren’t cooperating when he asked them to move back should need to happen. It happened because that group of people on the bus didn’t understand that having a bus with people packed in like sardines gets more people to where they need to go. When you’re considering a metropolitan transportation system, I’d like to think that you can condense everything into being about a single number - number people transported some distance in some period of time. That is,

MTA metric = ((# of people on the bus) * (miles traveled by the bus with those people on board)) / (how long it took)

Now, even though it doesn’t really seem like it when you’re stuck at a stop for 3 minutes instead of 30 seconds, maximizing the # of people component is actually your best bet for maximizing this number. As long as you’re adding people faster than you’re adding time, you’re doing better. It’s odd to think about, but those few minutes that seem like an eternity are actually the system doing a good job. But, not to neglect the human aspect to all of this. The people were complaining because they needed to get to work. I really do find it funny to think that if they were the ones waiting to get on the bus, they’d really be hoping that they’d make it on. I’m a cynic, but I’m also right. In any case, I think that this dissatisfaction is as a result of ignorance and lack of understanding rather than the system being “soooo terrible”. And I think what’s not understood is how we ended up where we are - with crowded buses and trains and cars sitting bumper to bumper for no real reason besides volume on the road during rush hour.

How did we end up where we are? My short answer is greed. More specifically, corporate greed, but I guess that isn’t wholly independent from individual greed. Let’s look at rail systems as a specific case. In general, I’d say that they’re pretty efficient - especially when you consider Maglev technology that’s become popular in Asia. There are fixed stations, and movement between those stations can happen extremely quickly. In addition, they’re a relatively high capacity mode of transportation at least in the sense that there isn’t all that much wasted space. Why then are we more likely to take a car somewhere than a train? Well, the first two thoughts that come into my head are that cars provide flexibility for start and end points and that people value personal space. But that answer is a cop out - it’s the easy reasoning.

Disclaimer: the story I’m about to tell might be cherry picking a story to fit my narrative. Even if it is, the story is true and it’s implications have been impactful. So, the actual answer to the question that I posed before(cars vs trains) is that during the 1940s oil, steel, and rubber companies attempted to systematically dismantle rail based public transportation systems. There were efficient light rail systems that allowed for quick and easy travel. Why get rid of them? The motivation is simple economics. Cars and buses were also constructed from steel, but their useful lives were generally shorter than trains. In addition, their fuel consumption was significantly higher. It follows that having more cars and buses on the roads would create demand for steel and oil, which would in turn create profit for those industries. The logic is sound. Anyone with the objective of maximizing their profit would have taken the same steps. But that’s the issue. Maximizing profit - staying true to the capitalist mentality doesn’t ensure that the overall outcome to society is optimized. We find ourselves, 60 years later, not only highly dependent on fuel(we’re getting closer to independence) but sitting in traffic for hours every day. For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that an hour of someone’s time is worth $10. That’s a low number, but 10 is round number. Ok, and let’s suppose that people spend half an hour per day in traffic as they commute, as they go to the store, as they travel to visit friends. Finally, let’s suppose that there are 50 million(~15% of the US population) people who do this 5 days each week. How much money is wasted on those collective 30 minutes per day? It’s $250 million per day. $1.25 billion per week. $65 billion per year. Now, of course, $65 billion per year isn’t all that much money, but remember that the numbers that I used were a low and conservative estimate of the actual waste. What are the actual numbers?

All of a sudden, we’re looking at a massive cost. And I don’t mean to say that the growth of the automobile industry has cost us significantly more than it’s been worth in travel inefficiency and environmental impact. What I mean to say is that it’s worth considering where we’d be if we had taken a different path. Could we have maintained the privacy and freedom to choose start and endpoints that cars have provided? I’d say yes. I’d also say that we’d have been able to find ways to do it extremely efficiently. Would we have lost out on the jobs and technology that have developed as a result of the success of the steel and oil industries? Also, yes. But that’s just it, I have an opinion on which option would have served us better 60 years down the line. Was that consideration present in the minds of the management teams of the big steel and oil companies? I suspect yes, but the fact is that cash is king and greed wins.

There’s also another dimension that I haven’t really touched on - automation. The fact that trains can be operated by computer systems fairly easily because they travel on fixed pathways. Self-driving cars seem to be the future of the car section of our transportation sector, but do they make sense either? On one hand, moving the operational control of vehicles out of the hands of easily distracted and fallible humans and into the hands of computers would almost certainly allow us to raise speed limits, reduce the need for traffic lights, and reduce the number of accidents in general. On the other hand, implementing a computer driven system in the same system that there are human-driven vehicles seems foolish. Not to mention that people enjoy having control and that many people enjoy driving in and of itself.

My sense is that we would be much better served if there were a system that cars or pods or whatever personal vehicles we end up using could lock into and then be transported at high speeds, like a train, until needing to move locally again. Think of something along the lines of moving walkways that have become popular in airports. Highways were intended to serve the purpose of providing these sorts of channels. On one hand, they’ve done that, but I’m certain that we can do better. We can do something - to bridge the gap between the efficiency of trains and the independence of cars.

Looking to the future:

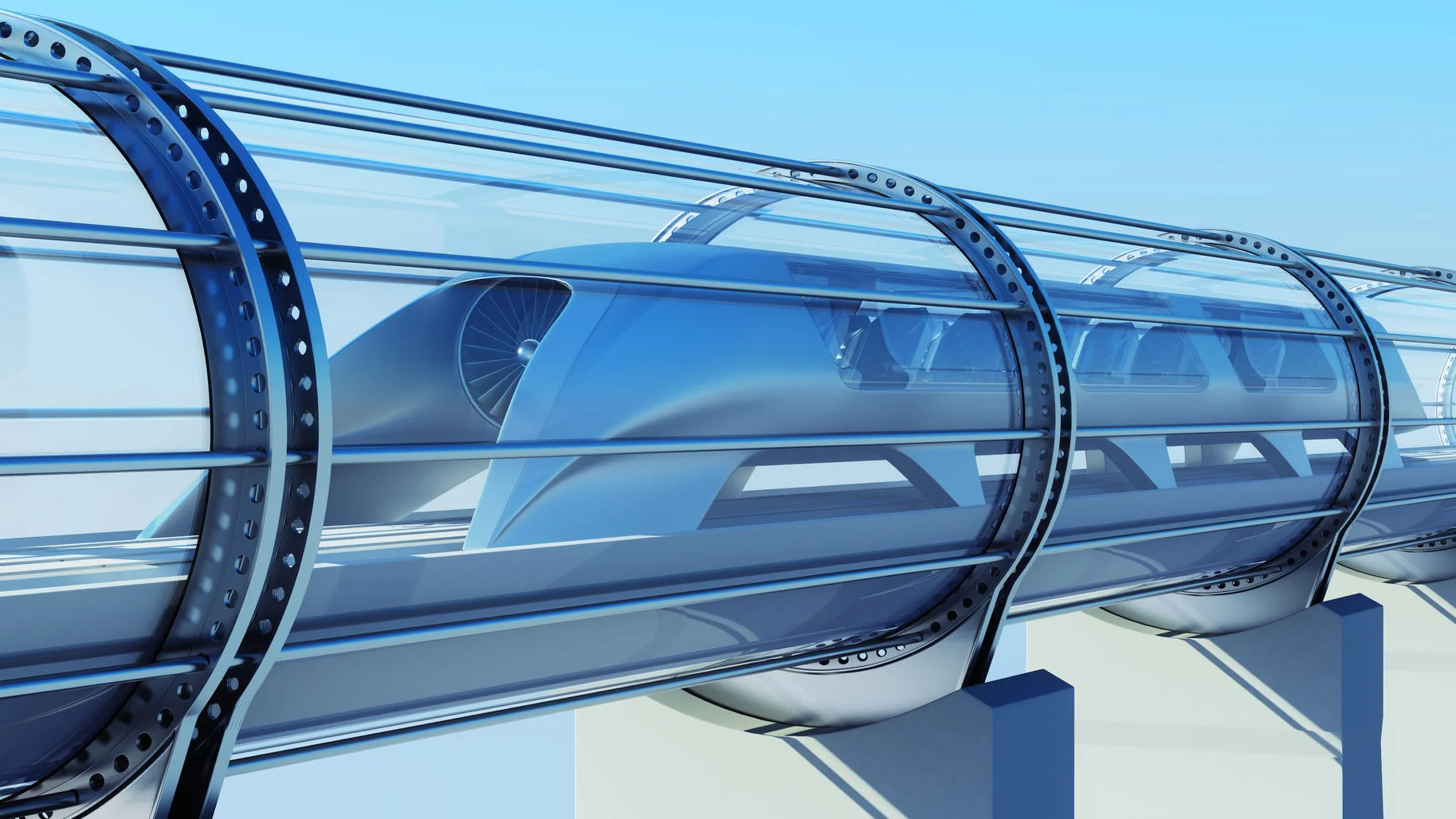

So, let’s move away from all of this philosophical and idealistic talk. What are we actually capable of striving towards? How can we best apply the technology that we have available to achieve better? 20 years down the line, I think that we’ll be completely independent from fossil fuels. Maybe sooner, maybe later, but that isn’t important. What’s important is that any proposed solutions must be conceived from within that framework. We know that maglev is drastically superior to wheel-ground contact. So, where does that leave us? I think that we need to if the direction of exactly what I mentioned before - individual pods that lock into a larger system. The personal space aspect of traveling by car can be retained. There would need to be a docking station in or near living spaces and everywhere else. Designing an infrastructure system for the transit of these pods that spans the same amount of area as roads do would be relatively straightforward. The hyperloop concept is the closest I’ve seen to implementation of such a system; and it is clear that it will be implemented in the near term. But I think we need to start putting together something that will be capable of replacing cars and roads as we know them. So, while I’m certain that the technology is there or will be there, the real work is going to be in removing the political and corporate roadblocks to making it happen. That’s a much more difficult problem, but if we’re going to be intelligent about the paths that we take as a collective moving forward, it’s a problem we’re going to have to solve. It’s not within the scope of what I’ve aimed to cover here, so I’ll save it for another time.