“For something that is so integral to shaping our daily lives, most people do not take the time to understand the subject deeply.” I believe that there’s something natural and important about having a childlike curiosity about the world. That sense of wonder that is so quickly lost as we age is the very thing that drives the world forward. It’s the force behind the formation of ideas and knowledge. It drives us to ask about why things are the way they are? About how can we make them better? Life as we know it, whether you’re aware of it or not, is governed largely, perhaps completely, by economics. In the same way that Physics is the central discipline within the physical sciences, Economics is the central discipline within the social sciences. So, it’s time to be curious and struggle for answers. The same way that we had to jump and fall to learn about gravity, we’ve had to lose money or miss out on opportunities to learn and understand the forces that govern our world. I don’t want to jump into “supply and demand” or “Real GDP” or “inflation”. I’d like to talk about why the things that exist, well, exist. I am by no means an expert, and my word is not law. Furthermore, my ideas are not my own – they belong to hundreds of economists over hundreds of years. This is just my perspective on their thoughts with a few flavors of my own sense of the future.

My first instinct is to start with thinking about money, but I don’t think that’s the right place. I think the most basic place to start is with the idea of an event best known as a transaction. Everything that happens from rain to “WWE Monday Night Raw!!” is ultimately a transaction. Time can be exchanged. Materials can be exchanged. Words can be exchanged. If you really start boiling it down, everything becomes inputs and outputs. In mechanics, they’re collisions. In chemistry, they’re reactions. In people, they’re interactions (Now of course there are cynical lines of thought, such as that every human interaction is transactional – I don’t want to think about that right now.) Without falling too far into the philosophical rabbit hole, the basic economic unit to consider is transactions. Some things are relatively simple while others are more highly complex, but everything that I’ve encountered so far fits into that framework. So what is the point of transactions in the context of economics?

Maybe the best way to approach answering that question is to ask what would the world look like without transactions. Well…if we don’t consider planting corn an investment transaction, then the logical next missing piece is that you can’t get corn from the farmer. Not only can you not get corn from the farmer but nor can anyone else. Someone who produces something is not capable of sharing it with anyone else. If they can’t share it with anyone else, they might as well only make enough for themselves. So, for everyone to survive, everyone needs to have their own plot of land that’s large enough to grow/raise however much food they need to survive. If you grow more than you eat, it goes to waste. Bad harvests mean that people starve. Has this started painting a picture in your head? It's basically a very long time ago when the life expectancy was relatively low and that society was primitive at best. I just used the word society, almost unwittingly, but maybe that’s the next place to go. The very idea of farming as an alternative to hunting and gathering lends itself to something. That something is trade.

Trade is just a transaction. “You grow this, and I’ll grow that. When the Harvest comes we can trade what we’ve grown.” Now there are two farmers. Then there are three, four, forty-one, and so on. The single farmer has become a network of farmers that are planning and interacting with each other. Out of this shift comes the birth of an economic structure – a market. “We should all gather on Saturday to exchange our harvests at a central location. It’ll be much easier than travelling to each other’s farms one by one.” The purpose of markets is to lower the cost of transactions, the basic economic building blocks. I think of the appearance of markets as something revolutionary to the economic world – as revolutionary as the assembly line or the computer. Okay, we’ve got transactions and markets. What’s next?

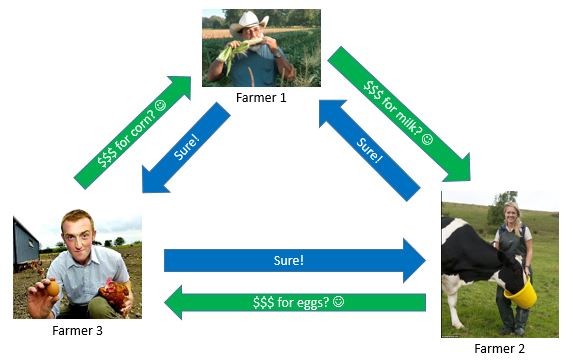

Moneeyyy! Here comes the moneyyyy. Money money money money money money. Money talks. Dolla dolla bill yo. What is money? Money is another way to lower transaction costs. I going to skip over why lowering transaction costs is a good thing, not because it’s obvious (it kinda is), but because I skipped over it before by simply saying that markets were revolutionary. To be clear, markets are revolutionary because they lower transaction costs. Money is similarly revolutionary because it lowers transaction costs. Money achieves this by providing something that markets alone cannot - the ability to exchange goods/products/services with someone, another farmer, even if they don’t have the exact product that you’re interested in or vice versa. I suppose the best way to explain why this is important is to draw a picture. Once upon a time there were three farmers…humor me. Farmer 1 grew corn. Farmer 2 raises cows that produce milk. Farmer 3 raises chickens that produce eggs. Farmer 1 wants milk to go with his corn. Farmer 2 wants eggs to go with his milk. And Farmer 3 wants corn to go with his eggs. Farmer 1 asks farmer 2 to trade him some milk for some corn. But farmer 2 doesn’t want corn, so he says no. Farmer 2 goes to farmer 3 and asks to trade some milk for some eggs. Farmer 3 doesn’t want milk, so she says no. Guess what happens next? That’s right! Farmer 3 goes to farmer 1 who says no because he doesn’t want eggs.

No one wants to bear the cost of holding onto something that they can’t necessarily use. Maybe Farmer 1 goes to farmer 3 and says that he’ll trade some corn for some eggs. Then he has to take those eggs to farmer 2 and ask to exchange them for some milk. Now everyone is happy, but this entire process has become messy.

That’s where money comes in. Money allows people to exchange what they produce for a product that everyone is willing to trade for. This messy scenario turns into something very easy. For the sake of simplicity let’s just say that you can go to “a market” and exchange what you produce for money. Then you can take that money wherever you like and exchange it for whichever goods you like. If you’re looking for eggs, go exchange your money for eggs. If you’re looking for milk, it costs this much money per gallon.

Having an intermediary good makes a market much easier to operate. Much easier equals much cheaper for everyone involved. Cheaper is good. Markets reduce the cost of transactions. Money is a special type of good that reduces the cost of transactions especially in a market with multiple goods. What’s next?

What’s next is potentially the most complex and important piece of this economic puzzle – Credit. Credit is the ability to borrow money now in exchange for paying it back later – generally plus interest. Why is this more complex and important? This thing all devours: Birds, beasts, trees, flowers; Gnaws iron, bites steel; Grinds hard stones to meal; Slays king, ruins town, And beats high mountain down. The player three that has entered the game is time. Before we even think about “the Time Value of Money”, I think that it’s better to explore time from a simpler approach. Sharing. Borrowing is allowing someone else to use what’s yours. Sharing, as we all hopefully learned in kindergarten, is a special case of borrowing. It’s a case of borrowing where the interest that is charged is your internal struggle to trust someone else with something that’s yours.

You tend to watch the other kid very closely when they’re playing with your toy. There will be hell to pay if they break it, lose it, damage it, do anything that you wouldn’t do with it, etc. All of those things lumped together in the context of money become realized as interest. Interest is just the price that has to be paid to borrow someone else’s money (toy) for some period of time. The longer they have your toy, the more you’re going to be concerned that something will happen. In the same way, the longer someone is borrowing your money, the higher the interest that they have to pay you because there’s more “risk” of something happening – there’s uncertainty about the future.

Now we can talk about the time value of money. The time value of money boils down to the very simple idea that money right now is more valuable than the same amount of money at some point in time in the future. Perhaps the easiest way to solidify this is to jump back to the toy analogy. Having the toy that you want is more valuable than a promise from your parents that they’ll give it to you for your birthday. Now means control. Now means certainty. The future is unstable and unpredictable. In the case of money, this control is valuable. This control is what allows you to go to the grocery store for corn, milk, and eggs – right now. If you had to delay going to the grocery store, you might get hungry – a cost. There is a cost to money that is only available in the future. I’m repeating myself, but hopefully the concept is clear. Money now is more valuable than the same amount of money in the future. This is distinct from inflation, though that is not to say that there are no links between them. Perhaps equally importantly, this is not distinct from the idea of opportunity cost. I don’t want to discuss opportunity cost too deeply given that I’ve aimed to avoid “inflation” and “supply and demand”. Here’s a brief summary:

Opportunity cost is the coulda-woulda-shoulda of economics. If instead of letting someone borrow your money you had kept it, you would not have been hungry. The cost of letting someone borrow money was your hunger and any other benefits you could have purchased with the money had you not let someone borrow it. Similarly, the opportunity cost of keeping your money would be the amount interest that lending the money would have earned you.

I mentioned before that what makes credit complex is time. While this is true, it would be more accurate to say that what makes credit complex is that it’s very hard to agree on how time will affect the value of things. Interest rates on mortgages, on cars, on government bonds are selected based on a consensus on both sides – the person borrowing and the person lending. If you don’t agree that 28% is a fair rate to pay on your mortgage, you wouldn’t agree to pay it. Similarly, a bank wouldn’t agree to give you money to buy a house if you were only willing to pay them .01% back on money that you would be borrowing for 20 years. Coming to this consensus is difficult and is what really makes credit tricky. At the same time, misuse of credit can prove to be extremely dangerous. However, despite complexity and danger, credit also accomplishes something extremely powerful. Credit allows spending to increase without an increase in production.

Let’s jump back to the Farmers. The total amount of money or “value” in the 3 farmer economy is the value of the corn, milk, and eggs that they produce. They can only spend as much money as they’re able to exchange their respective goods for. So, if they each produce $100 worth of goods, there would be $300 ($100 x 3) in their economy. They each have the ability to spend up to $100 on whichever goods they’d like to. So, this $300 total value passes from farmer to farmer harvest after harvest, assuming harvests don’t change in size. What happens when we introduce credit? Let’s say that if a farmer has $100, someone is willing to let them borrow $20 – 20% of how much money they already have. Before, harvest after harvest, the $100 worth of corn allowed farmer 1 to plant seeds for another harvest worth $100. With credit, farmer 1 has access to $20 extra dollars. For the sake of the example, we’re going to have to assume that the farmer has a way to produce value with those $20 extra dollars that allows him to pay back the $20 and some interest. Using credit to create more value is what makes it powerful.

Well, farmer 1 grows corn. He spends those $20 extra dollars to buy corn seed that will allow him to grow and harvest corn worth $40 on top of the $100 that he was growing before. So, the harvest comes and the farmer sells the corn that he grew for $140. He uses the first $25 dollars to pay back his debt plus $5 in interest. Then he spends $100 on the milk that farmer 2 is selling. And at the end of the day, he has $15 extra dollars left over. Now if we look at the entire farmer economy, there are $315 instead of $300 because of credit. Farmer 1 could use those $15 to buy more corn seeds, save them in case there’s a bad harvest, lend them to another farmer, or any number of possibilities. To reiterate what I said before, what makes credit powerful is that it allows people to use good decisions to increase value, not just for themselves, but for the entire economy.

Before we move past credit, there’s a critical point to focus on. Credit only helps growth when it’s used to enable good decisions. I think the simplest example is if he had chosen to do nothing instead. When the next harvest comes around he’ll still be able to sell the corn for $100. But, now he has to pay back his debts. So, he pays back the $20 he borrowed plus $5 in interest. What changed? What changed is that now he only has $95. Instead of buying $100 worth of milk from farmer 2, he can only buy $95 worth of milk. Not only does he not have as much milk as he wants, she also won’t have enough money to buy $100 worth of eggs from farmer 3. In the same way that there was the possibility of farmer 1 using the $15 that had been gained through the use of credit, misuse of credit can decrease value in the economy.

You may have realized, I have at least, that I haven’t talked about where those extra $20 are coming from or where the extra $5 are going when the money is paid back. This was intentional. The world of credit is what makes up the bulk of our financial system. In short, money and credit are two special types of goods that are exchanged on both massive and small scales instead of trading corn, eggs, and other goods directly. It follows that understanding money and credit are two of the most critical pieces to understanding economics. Transactions are the basic economic unit. Markets exist to lower the cost of transactions. Money is a special good that is used as a medium of exchange to reduce the cost of transactions even further. Credit is another special good that allows transactions to take place, even if there isn’t money available right now.

Before I bring this to a close, there’s one more topic to discuss. The next critical concept is productivity. I mentioned that credit helps growth when it’s used to enable good decisions. What are “good” decisions? I said that farmer 1 could spend $20 on corn seed and grow $40 worth of corn. A “good” decision in an economic sense is to use less to create more. $20 is used to create $40. Without moving to far away from that, productivity is using the same to create more. In the farmer example, farmer 1 thought that he could produce value of more than $25 with $20. Simply, the productivity of farmer 1 was higher than the cost of borrowing. Since this may seem a bit ambiguous, I’m going to use another example (I promise, it’s the last one).

Farmer 2 has cows that produce milk. Farmer two is able to produce and sell $100 worth of milk each harvest. Suddenly, she has an idea that allows her to milk the cows faster/cheaper/better. Instead of $100 worth of milk, now she’s able to produce $105 worth of milk. Much like farmer 1’s use of credit, farmer 2 ends up with extra money left over. $5 to be exact. Productivity is another force that is capable of driving economic growth. Productivity is driven by good ideas, by innovation, and by technology. The things that we choose to do, how we do them, and the tools that we use to help are the core of defining how productive we are. Over time our productivity generally increases because we tend to gain knowledge over time. With more knowledge we are able to conceive better ideas and create better technologies, which allow us to gain more knowledge and so on.

Okay. That’s it. I’m done explaining the foundation of economics. A quick summary: The basic unit of economics is transactions. Markets exist to lower the cost of transactions. Money is a special kind of good that is used as a medium of exchange to further lower the cost of transactions. Credit is another special good that is used in place of money to allow transactions to take place when money isn’t available right now. Productivity is what increases as we gain knowledge and improve technology that allows us to produce things more efficiently. Understanding these basic economic structures and drivers is foundational to understanding economics. I’ve oversimplified them to some degree, but it’s a start. There’s much more to think about.